The invitations from rankers to complete “reputation surveys” are, once again, making rounds. It’s as good an occasion as any for a little reminder of the history of this practice.

This time, as many times before, I can’t help but think of the American classicist William Arrowsmith, who referred to such surveys as “quantified gossip” (back in 1976, in the Preface to Patrick Dolan’s The Ranking Game). Criticizing the opinion poll-based rankings of graduate departments published by the American Council on Education (ACE) some years earlier, Arrowsmith wrote:

They purport to represent “expert opinion”—that is, the judgment of the professoriate on its own performance. The rankings doubtless indicate something, but as an index of quality they are of extremely dubious value; in fact, they are little more than quantified gossip or hearsay. /…/ Even administrators, that is, can grasp, beneath all the plausible talk about the wisdom of having peers judge peers and the incontrovertibility of “expert” opinion, the profile of still another form of institutionalized and bureaucratic “bad faith.”

Quantified gossip, bureaucratic bad faith, or perhaps something else, the opinion poll known as the reputation survey is possibly the most enduring method of quantifying the differences in quality among higher education institutions (whatever this may mean; going into a discussion on how “quality” is to be defined is beyond this post). It is often criticized as simultaneously the least “objective” and the most methodologically problematic among the measures of quality used by rankers.

Be that as it may, here I do not intend to go into a discussion of the methodological (in)validity of such polls (others have done that). Instead, I want to share a couple of details about their history.

According to Hammarfelt, de Rijcke, and Wouters, in the academic context, the reputation survey was pioneered by the social psychologist James McKeen Cattell. Back at the beginning of the 20th century, Cattell was interested in measuring the reputation of American scientists, and his thinking was largely influenced by the earlier work of statistician Francis Galton and the eugenics movement. For Galton, reputation was “a pretty accurate test of high ability” and he defined it “as the opinion of contemporaries, revised by posterity – the favorable result of a critical analysis of each man’s character, by many biographers” (quoted by Godin).

A conceptual side note: we could say that, unlike one’s ability, which could in principle be established solely by observing a person independently of others, reputation is as a rule a social thing. Put somewhat crudely, if you were the only person in the world, you could still have abilities, but you could not have a reputation. For that to be possible, you would need others. Hence, an opinion poll offers itself as a meaningful method of determining (or, constructing, to be more precise) one’s reputation.

For Cattell, however, reputation was of interest as a way of capturing the “eminence” of individual scientists, rather than as a way of comparing departments or universities (at least not in any direct terms).

The first opinion survey aiming to quantify the reputations of higher education institutions was probably the one circulated by Raymond M. Hughes, then President of Miami University, in the 1920s (probably, in the absence of evidence to the contrary).

Curiously, Hughes did not mention Cattell or any other previous such survey, but he did make a passing reference to a “British ‘Year Book’ on Education” in which “among much other valuable information, we find listed the British institutions maintaining strong departments in each subject.” He further adds, “If such a list can be published in Great Britain, surely one might well be published in America.” I wish I could say something more about said British yearbook, but unfortunately, I have so far not managed to get hold of it. Indeed, it could be that similar surveys were being circulated in other parts of the world around that time, or earlier, though I have no evidence of this.

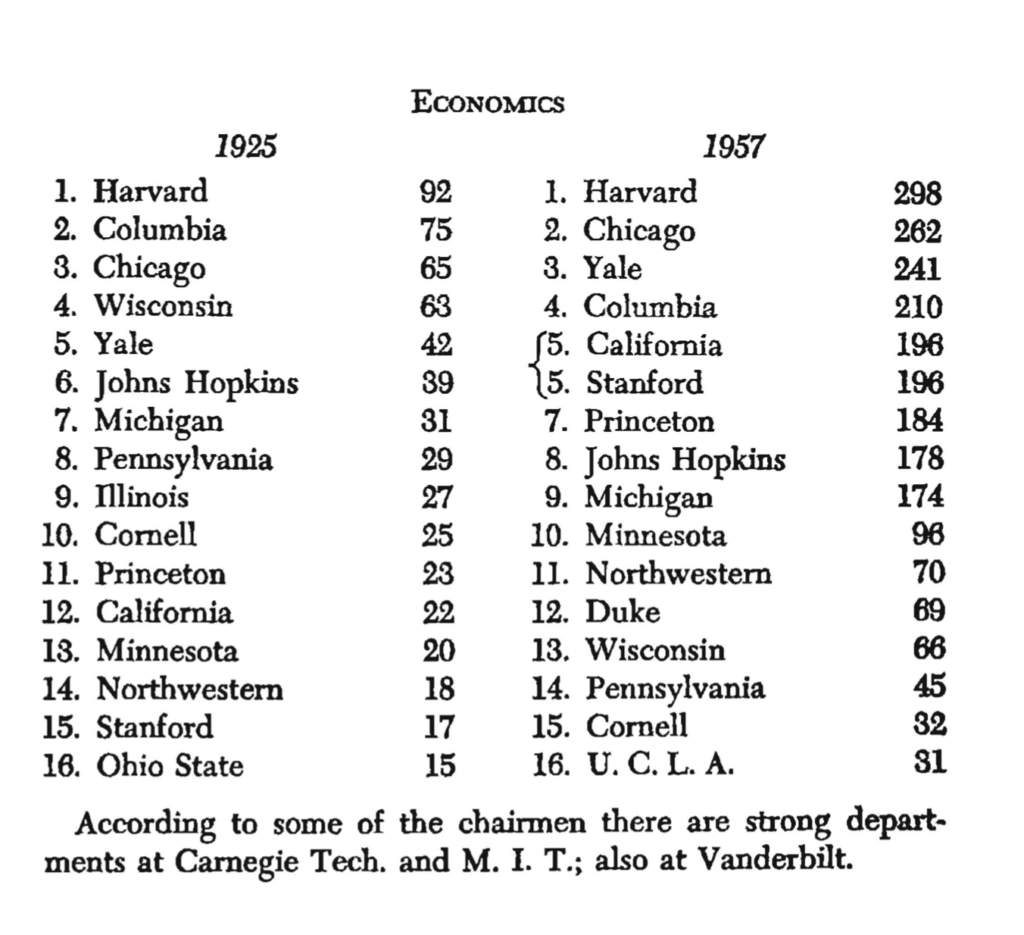

Anyhow, Hughes used the data collected through his opinion survey to compile rankings of graduate departments, which he published in A Study of the Graduate Schools of America (1925). The whole report is available online, in case you want to browse through it. I especially recommend the introductory parts, in which he also explains the motives for the study and the method. The rest of it are tables, such as this one:

It is also notable that, in contrast with reputation surveys of later decades, those circulated by Hughes were not in any way anonymous. In fact, all the individuals (men, of course) completing the questionnaire would be listed in the report, next to the ranking of departments in their field of study. Here we see a link with Cattell, albeit only an indirect one: the professional authority (and reputation, arguably) of the individuals partaking in the nationwide “gossip” exercise would reflect on the trustworthiness, validity in some sense, of the reputations thus constructed.

Hughes would repeat the survey in 1934, this time as the chairman of an ACE committee. He seemed a big fan of repeating the surveys, not least because he thought it was somewhere important to capture changes in departments’ relative reputations over time. It may seem like a trivial matter from today’s perspective, but back in the day things were different, and most people in and around academia didn’t care as much about such things as how best to measure the reputation or excellence of higher education institutions. Moreover, the reputation of a university wasn’t thought of as something that could change on an annual basis.

Then, in 1959, Hayward Keniston published his Graduate Study and Research in the Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania, whose appendix contained an updated ranking of graduate departments, based on the reputation survey he had himself conducted. He additionally compared his scores with those calculated by Hughes in 1925, and even combined all the departmental scores for each university. Here is one of the departmental rankings (economics), followed by the combined standings:

Then came the 1960s and with them further contributions to the reputation survey genre. Again, the ACE was in the driving seat, although this time the initiative (and funding) came from the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Health, and the United States Office of Education. This survey was bigger, at least when it comes to the number of respondents (around 4,000) and the number of institutions included (106). The final report, An Assessment of Quality in Graduate Education (also known as The Cartter Report, its author being the economist Allan M. Cartter) sold a whopping 26,000 copies (according to Webster), which was considered remarkable for a publication of that kind. The ACE repeated the survey, published the results in 1970, and then again in the early 1980s.

Reputation survey was also the method of choice of U.S. News & World Report when they first ventured into the college ranking business in the 1980s. For the first edition of rankings, they approached 1,308 four-year college presidents all over the United States whom they asked to name “the nation’s highest quality undergraduate schools.” A total of 662 replied. Now, I do not know if U.S. News was in any way inspired by the surveys previously done by ACE or someone else, although as a magazine, they had been well-versed in opinion polls of various kinds. Suffice it to say that, to this day, U.S. News relies on the reputation survey (together with other kinds of data), although the survey itself has undergone a great deal of change since the 1980s.

The creators of the first global ranking of universities (Academic Ranking of World Universities, aka Shanghai Ranking), published in 2003, take pride in the fact that they do not rely on such questionable methods as the reputation survey. I can’t say why the people in Shanghai, back in the early 2000s, opted for counting Nobel Prizes, bibliometric data, and similar, instead of running an opinion poll, or whether they even considered it. But one thing is for sure: surveying academics on a global scale back in the early 2000s would have been much more demanding than it was to obtain already existing bibliometric data. As it often happens, resources and practical aspects play a much more important role than we like to think.

And yet, eventually, the quantifying gossip has found its way into global rankings as well. Today, some of the biggest producers of these rankings—Quacquarelli Symonds (QS), Times Higher Education (THE), and U.S. News & World Report (USN)—draw some of their data from such surveys. The scale of the operation is beyond anything that could have been imagined during the 20th century, not least because the technical capacities would not have allowed it. Just to illustrate: THE boasted almost 30,000 responses from 159 countries in the last round of their reputation survey.

Now why they choose to keep the opinion poll, given both the criticism it attracts and how resource-demanding it is to maintain it, is an interesting and important question. Maybe something to get busy with some other day. (I hint at it here, although there is of course more to it.)

In the meantime, it may be worthwhile to keep in mind where this method comes from.

Note: some of the ideas (and most sources) shared in this post are based on the work done by Stefan Wilbers and myself, which we published in an article: The emergence of university rankings: a historical‑sociological account (Higher Education, Vol. 86, pp. 733-750).

Photo: Llamas (or alpacas?), Livigno (Italy), January 2023. © Jelena Brankovic